Texas Toast. Boston Cream Pie. Chicago deep-dish. Any time a food and a geographical location get married, there’s bound to be a little bit of drama. Emotions come into play over whether the food that’s claiming to be Chicago-style pizza can rightfully wear the crown. Suddenly, the food in question isn’t just a slice of pizza, bread or pie–it’s a slice of Chicago. (Or Texas, or Boston.)

So instead of is this food a tasty food, the question becomes does this version of this regional food accurately represent who we are as people? Which, uh, gets pretty loaded.

Such was the fate of the mostly-forgotten Bedfordshire Clanger–a hotly-debated hand pie from Victorian-Era England.

These days, political drama is always, always, always high-stakes, life-changing, and emotionally exhausting. So take a moment to waltz with me, hand-in-hand, down this delightfully low-stakes memory lane in which a bunch of Bedfordshire residents once got real up in arms about whether or not their beloved pie officially had jam in it.

First off–“Bedfordshire Clanger”? What are these words?

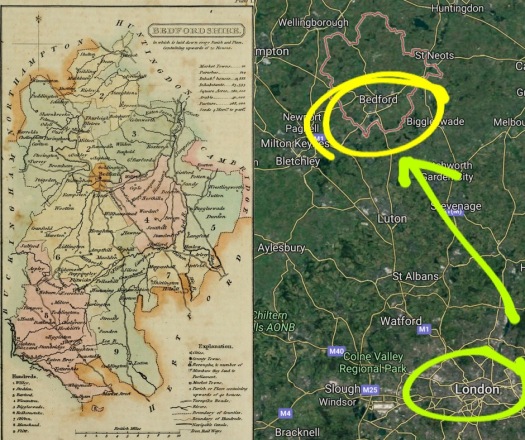

Where is Bedfordshire? Well, you know how England loves their shires, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that it’s a county in East England about a 40-minute train ride north of London.

Okay, then what’s a Clanger? Excellent question. It’s definitely a kind of hand pie made with a suet crust. It almost definitely involved pork and onions. (Suet, if you’re unfamiliar, is typically the fat found around the kidneys of a cow; a suet crust is a pie crust made with suet instead of cold butter.)

But the main debate happens around two styles of the iconic Bedfordshire Clanger:

Style 1: A simple, no-frills, pork-and-onion hand pie. Done and done.

Style 2, which is the far-weirder version: A long pie tube that has an internal divider. One side of the pie is a savory pork-and-onion pie. The other is sweet, and usually filled with jam.

We’ll put aside “who’s right” for a minute–and instead, talk about how the Clanger became such a Thing that the people of Bedfordshire felt compelled to slap their county’s name on it.

Why the Bedfordshire Clanger symbolized cleverness, frugality, and practicality

Way back in 1880, a political editorial in a newspaper got real sentimental about the “old-style roadman…a worthy public servant” in apparent frustration over paved roads, automobiles, and a generally faster pace of life. The author’s “pleasant picture” is as follows:

“He is a hale, rugged, bright-eyed man, face and hands tanned by the wind and sun and whirligig English weather of half a century. He is clothed in useful, hard-wearing fustian jacket, sleeved waistcoat, corduroy trousers, heavy hob-nailed boots, black felt or billycock hat, and a red-and-white spotted kerchief. He gives you ‘Good-day’ with a smile as he munches his ‘Bedfordshire clanger’…the frugal meal.” (1)

In other words, this fictional dude is such a good dude of the people, and he’s eating The People’s Meal to prove it–the incredible Bedfordshire Clanger.

But why was the Bedfordshire Clanger the meal of the people? For starters, it was “the most economical course that can grace a dinner-table…like the purse of Fortunatus, it shows no signs of depletion.” (2) Allegedly, though economical, it was also pretty delicious–in 1927, a ditch-worker, Mr. William Smith of Duloe, described the Bedfordshire Clanger as “a tasty and sustaining dish for the farm worker in peace time.” (3)

Aside from the obvious cheap-sustainable-meal points, its sentimental value was also off the charts. One 1911 paper included a piece of local news in which a soldier of the North Hamptonshire Regiment thanked his friends for their thoughtful care packages, but added that “he should love to get a ‘Bedfordshire Clanger.’” (4) As in, “Hey, thanks for the letters, guys, but what I really want over here is that one weird pie.”

The Clanger was also a dish surrounded by funny stories you could imagine being told over a holiday meal or after a round of drinks; one Mr. Bob Turner reported an “amusing anecdote” for a 1949 paper about an anonymous man:

“Every Monday his wife sent him forth on his week’s work with six clangers, one for him to eat each day he was away. Thus every time he ate a clanger he knew what day it was. But one day, being hungry, he ate two clangers at one sitting and arrived home on Friday instead of Saturday.” (5)

As you’d probably guess, the Clanger, apparently for rough-and-tumble military men and TV sitcom husbands, was not originally a delicate dish. The idea of the Clanger being hardy enough to survive getting “kicked about by the horses” (6), repeatedly thrown in the dirt (7), or “clanging” against “the cowshed door” (8) was a popular one. By all rights, these were sturdy pies for hardy men.

But from where are these pies materializing, just to be thrown against barn doors?

The clever women who made the Bedfordshire Clanger possible

As it turns out, behind most Manly Pies for Manly Men are resourceful women trying to feed way too many people on a tight budget.

Mrs. Hyde from Barton remarked in 1949 that “If I had as many shillings as I have made clangers I’d be a rich woman now.” (5) Bedfordshire Clangers also featured at the 1937 Bedfordshire Federation of Women’s Institutes annual exhibition, in which women “evidently well versed in the culinary arts” made foods that celebrated Bedfordshire’s history–and, undoubtedly, their role in it. (9)

But most impressively, an “F.G. Crouch” from a 1927 issue of The Bedfordshire Times And Independent shares a chat he had with one of their “oldest ‘parishionesses’” who got married in the mid-1850s; prime Bedfordshire Clanger time.

Her husband didn’t make a ton of money (though it’s unclear exactly how little), and the “parishioness” in question fed herself, her husband, and five children with, it seems, Bedfordshire Clangers:

“3lbs. of salt pork (commonest parts) at 41/2d. Per lb. was for the making of the clangers, with a bit of liver and fat occasionally. Her husband and eldest son went to work on many days on draining, etc., with a herring. Suet swimmers (lumps of dough boiled with the vegetables) were part of the week’s rations.” (10)

With all of the cooking responsibility and none of the money, life was difficult enough–but in Luton specifically (the largest town in Bedfordshire), women of the house likely had limited time, too.

Luton was famous for its hat-making industry, and this industry included women in a big way. Many women in Luton were working both in and out of the home, weaving fashionable hats that, according to historian John Dony in 1942, rivaled the hatmaking industries of New York and Paris.

A quote about Bedfordshire’s hat-making industry specifically:

“The number of people engaged in the ‘straw’ hat manufacture is 11,980 (8,283 females and 3,697 males) in Bedfordshire… It is probable that these figures do not represent the total number of females engaged in the ‘straw’ trade, for a considerable number of married women do ‘straw’ work in their homes.” (Jordan)

So if you’re the kind of gal with a family to feed and hats to weave, the Bedfordshire Clanger is sort of a godsend, whether or not it includes jam. These pies were traditionally made in batches and left to boil for 2-3 hours (11, 12)–the 19th-century equivalent of the Crock-Pot dinner.

This means that they could multitask. Once the pies were made and left to simmer, the dinner was more or less on auto-pilot; which meant it used all their resources, including time, as economically as possible.

As society–and availability of ingredients–shifted (3, 5), the Bedfordshire Clanger understandably fell out of fashion. But something about this dish was so regional, so nostalgic, that it refused to die a quiet death.

In which the Bedfordshire Clanger gets continually resurrected

Much like J.K. Rowling seems pretty unwilling to let Harry Potter gracefully assume the role of “old classic,” Bedfordshire residents didn’t want to let their precious pastry go.

The Clanger first made a big comeback in 1942 with Bedfordshire’s County Councils Emergency Meals Service (13), in which the local government noticed that wartime rations were fine-ish for English city-dwellers, but really threw the rural folks under the bus. To combat this, emergency kitchens popped up that would, apparently, feed everyone if some major crisis befell the county.

In addition to this worst-case-scenario infrastructure was helpful-right-now infrastructure, also known as daily pie deliveries. These so-called “cash-and-carry meals” were organized, cooked, and delivered almost entirely by the Women’s Voluntary Service; they took orders in the morning, cooked them, packed them in “heat-preserving containers,” and delivered them to most of the villages “between three and five in the afternoon.”

(That’s pretty impressive, especially given that they were only operating at about 15% capacity–if demand were higher, they could have opened more kitchens, and cooked/delivered the orders faster.)

Though apparently, these updated Bedfordshire Clangers were staunchly Style 1, given the reporter’s reluctance to confirm even the existence of a Style 2 recipe, and the description of the modern-day clangers as “pastry…[filled with] one and a half ounces of meat, strictly apportioned.” (13) This is likely because they were going back to basics, which meant taking a page out of that old parishoness’s cookbook–literally. Limited food and plenty of mouths to feed? Don’t bother with jam.

After war-time rations vanished along with the war, the 1950s got nostalgic for the old days. In 1951 and 1956, a few cookbooks inspired by old-timey recipes–most notably Gladys Mann’s “Good Food From Old England” and David Langdon’s “Mr. Therm Goes County”–published recipes for the Bedfordshire Clanger.

Interestingly, both of these recipes advertised the Bedfordshire Clanger as its Style 2 version–one end filled with pork and onions, the other filled with jam. (11, 14) After all, with wallets and pantries no longer bound by wartime scrimping, jam was likely no longer an impossible indulgence; instead, it was an indulgence sorely wanted.

So of course a warm, comforting cookbook with nostalgia-based recipes would go for the version of the Bedfordshire Clanger that wasn’t quite so bare-bones.

And as more and more time passed by, the Bedfordshire Clanger stopped being a tangible, everyday, frugal meal that people actually remembered eating, and it became more of a concept.

People started writing in to papers asking for proof that it existed because “the girls and women I work with do not believe me? They have never had one.” (15) And this was when things started getting messy; as newbies started looking for definitions on what this weird pastry called a “Clanger” was, suddenly everybody had an opinion.

That’s not a real Bedfordshire Clanger!

From the newspaper clippings I pulled, the breakdown of people asserting that a “real” Bedfordshire Clanger was Style 1 vs Style 2 worked out to exactly 50/50.

One man was thoroughly upset that anyone could possibly think a Bedfordshire Clanger involved jam in any way:

“Sir.–The Bedfordshire clanger, as made in the north of the County upwards of 100 years ago, was a paste made of flour and water, which enclosed salt pork, sliced onions and potatoes, boiled, and eaten cold with bread. About 70 years ago a lad who was driving plough hung his basket containing a clanger on the hames of one of the horses of the plough team, but on arrival in the field the basket was missing. Going back to look for it, he found that after the basket had fallen and been kicked about by the horses, the clanger was still intact–or so he told me when he was an old man.

The original clanger was made round, but those of later date, with suet in the crust and containing jam in one end must be the “de luxe” model.” –Colmworthian, 1954 (6)

Another was horrified that a restaurant would dare to serve a Bedfordshire Clanger that had no jam:

“I, with all humility, in the interests of historical accuracy, and for the honour of Bedfordshire, would maintain that whilst the dish quoted was good, it was a very remote cousin of the real Bedfordshire Clanger.

The old folks would know that the Bedfordshire Clanger is a boiled suet crust roly-poly pudding, the left half charged with chopped meat, potatoes, bacon, and onions, and the right half with jam content.

Modern workers probably fed from a machine canteen with synthetic foods will not remember the old builders who brought their clanger to work and half-an-hour before dinner time carefully placed it on top of a half-bucket of quicklime and enjoyed, piping hot, both right and left half of a natural nourishing and extraordinarily tasting meal.

Had the good Doctor tried the right half of a real Bedfordshire Clanger, I am sure he would have clamoured for the left half.” –F. Wilson, 1950 (16)

Notice how, weirdly, both of these stories invoke very different rosy-glasses versions of the past?

The guy who said “of course no jam” fondly remembers the clanger withstanding a horse’s kick, and eating this sturdy pie cold; virtues of the toughness of yesteryear.

The guy who said “obviously yes jam” waxes poetic about old builders carefully placing their dinner on top of a bucket and enjoying a “piping hot…natural nourishing and extraordinarily tasting meal.” Uh-huh. Something tells me this second guy’s never worked on a farm. (To be fair, neither have I, but come on. Piping hot?)

And this trend continued. Most of the hard-nosed, excuse me sir I really must disagree notes were totally soaked with nostalgia. The stories were tied up with important moments in their youth, or in the field as a farmer. For example, one man remembered the first time he saw a Bedfordshire Clanger–specifically, when he “was 12 years old, while I was watching our horsekeeper’s wife unpack his lunch in Hall Field, Podington.” (17)

Today, “correct” nostalgia aside, both types of the Clanger are equally steeped in Bedfordshire’s history–though the weirdness of the meat-and-sweet version has given it a life far beyond the one most of us would’ve expected from a pork and onion pie.

Contemporary versions of the Bedfordshire Clanger

Food-based media has a small handhold in the Bedfordshire Clanger game; on the most recent season of the Great British Bake Off (not available yet in the US, sadly), the contestants baked Bedfordshire Clangers as part of “Forgotten Bakes Week.” In the Food Blogosphere, Lorraine Elliott of Not Quite Nigella posted a recipe for Bedfordshire Clangers in 2015, which, interestingly, uses suet and butter.

And in England, the family-run Gunn Bakery (est. 1928) sells a range of traditional and newfangled Clangers. One is Indian-inspired (designed to appeal to “today’s youngsters”), with a savory side of vegetable curry and a sweet side of “refreshing Mango dessert.”

The Bedford Borough Council posts what would seem to be the official recipe–I mean, if it’s on the website of the effective Council of Bedford, it might be the last word on the matter. But their modern-day take is significantly fancier than anything their predecessors would’ve called a Bedfordshire Clanger, especially because it starts with premade shortcrust pastry, travels through a pork-onion-sage-apple-peas savory side, and ends with an apple-dates-orange zest dessert side.

Finally, Tastemade has a pretty hilarious version of the “epic” Bedfordshire Clanger, which they describe as “the OG fast food” and the result of “if a pasty, a sausage roll, and an apple pie had a baby.”

It gets funnier when you imagine a housewife with 9 kids, a farmer husband, a hat-making job, and zero dollars watching the video. Ah, yes. Bedfordshire Clangers–the ultimate indulgence. A guilty pleasure, these slow-simmered beef fat dumplings.

But also–this is the nature of the world. As cultures change, so does food. And that’s essentially why there was a small war in the The Bedfordshire Times and Standard over a “true” Bedfordshire Clanger.

Wherever and whenever you grow up, the first time you try a new food defines that food for you. Family recipes and preferences shape yours. And for the rest of your life, when you eat that particular food in that particular way–a pie, a barbecue sandwich, or a Bedfordshire Clanger–you’ll get a wave of nostalgia. A wave of “home,” whatever that is for you.

So when someone writes into a newspaper about a wildly different version of your Food Home, it makes sense you would read it and get indignant and protective. Because if your treasured food is changing, that means the world is changing. And maybe your home is changing, too.

But–and this is really the heart of food history–no matter how the world changes around you, your roots will always live on in your recipes.

References/Further Reading

Linked Sources:

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Bedfordshire.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, 31 Aug 2007. 23 Mar 2018.

Lemm, Elaine. “What Is Suet And Alternatives To Suet In British Food.” The Spruce. The Spruce, 04 Oct 2017. 23 Mar 2018.

Hughes, Claire. Hats. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017. Web. 23 Mar 2018. http://books.google.com

Jordan, Albert. “The ‘Straw’ Hat Trade.” The School World: A Monthly Magazine of Educational Work and Progress Aug. 1914. Google Books Web. 23 Mar 2018.

Bell, Bethan. “Women’s Voluntary Service: ‘The army Hitler forgot’.” BBC News. BBC, 9 May 2016. 23 Mar 2018.

Pemberton, Becky. “Best of Both Worlds: How to Make a Bedfordshire Clanger From Great British Bake Off 2017 Forgotten Bakes Week.” The Sun. News Group Newspapers Limited, 17 Oct 2017. 23 Mar 2018.

Elliott, Lorraine. “The Double Ended Bedfordshire Clanger!” Not Quite Nigella. Not Quite Nigella, 30 Jun 2015. 23 Mar 2018.

“Bedfordshire Clanger From Gunns Bakery.” Gunns Bakery. N.p., n.d. 23 Mar 2018.

“Bedfordshire Clanger.” Bedford Borough Council. Bedford Borough Council, 2018. 23 Mar 2018.

Tastemade. “Clangers.” Tastemade. 30 Aug 2017. 23 Mar 2018.

Hughes, Claire. Hats. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017. Web. 23 Mar 2018. http://books.google.com

Jordan, Albert. “The ‘Straw’ Hat Trade.” The School World: A Monthly Magazine of Educational Work and Progress Aug. 1914. Google Books Web. 23 Mar 2018.

Unlinked Sources:

- “Bedfordian’s Diary.” The Bedfordshire Times and Standard 23 Mar. 1945: 8. Print. (Quoting The Bedford Mercury 20 Mar. 1880)

- “Local Topics.” The Bedfordshire Times And Independent, 30 Jun. 1911: 8. Print.

- “Land Reclamation in Bedfordshire: Ditcher’s Complaint,” The Bedfordshire Times and Standard, 28 Feb. 1941: 10. Print.

- “Bedfordshire.” Bedfordshire Advertiser and Luton Times, 12 Nov. 1915: 10. Print.

- “Country Magazine Features Bedfordshire:‘Clanger’ Tales”, The Bedfordshire Times and Standard, 26 Aug. 1949: 8. Print.

- Colmworthian. “More About the ‘Clanger’”, The Bedfordshire Times and Standard, 5 Nov. 1954: 7. Print.

- “The Bedfordshire Crawlers,” The Biggleswade Chronicle, 24 Sep. 1954: 8. Print.

- Richardson, H. R. “The Clanger.” The Bedfordshire Times and Standard, 29 Oct. 1954: 7. Print.

- “Women’s Institutes: Fine Exhibition of Home Produce: A National Asset” The Bedfordshire Times and Independent, 8 Oct. 1937: 2. Print.

- Crouch, F. G. “Letters to the Editor: Bedfordshire Clangers.” The Bedfordshire Times And Independent, 11 Feb. 1927: 7. Print.

- “Fit For A Princess: Bedfordshire Clangers”, The Biggleswade Chronicle and Bedfordshire Gazette, 14 Sept. 1951: 3. Print.

- “Bedfordshire Dishes,” The Bedfordshire Times and Independent, 8 Oct. 1937: 2. Print.

- “The Clanger Brought Up To Date: Bedfordshire’s Popular Pie: Communal Cooking,” The Bedfordshire Times and Standard, 25 Dec. 1942: 6. Print.

- “Drop this clanger on the table!” Daily Herald, 27 Mar. 1956: 6. Print.

- Clarke, S.M. “Letters to the Editor: The Bedfordshire Clanger.” The Bedfordshire Times and Standard, 22 Oct. 1954: 9. Print.

- Wilson, F. “Letters to the Editor: The Bedfordshire Clanger,” The Bedfordshire Times and Standard, 3 Nov 1950: 7. Print.

- Cook, P. “Letters to the Editor: The Clanger.” The Bedfordshire Times and Standard, 29 Oct 1954: 7. Print.