It was half-past 6 on a truly gloomy winter’s night in Manhattan, and I was perched on a stool in one of the stark classrooms of the International Culinary Center, wearing an oversized chef’s jacket and trying my best to stay out of the way. Around me, four students in the Pastry Arts program whirled around with efficiency, weighing ingredients and assembling their mise-en-places for the dessert of the day: meringues.

The chef called everyone up to the front for her first demonstration, scraping some cream of tartar into the bowl along with her egg whites and powering up her stand mixer.

When everyone returned to their stations, I hovered nearby like a good little auditor. “Um…what is cream of tartar?” I asked, a little intimidated. “I mean, I know it stabilizes the egg whites, and I’ve used it, but I don’t actually know what it is.”

The chef smiled, apparently happy someone asked. “It’s powder from wine residue,” she said. “They first found it inside wine casks.”

I said some more-professional version of “Wait, what?” and added, “Then who figured out how to bake with it?”

She shrugged. “I’m more into food science than food history. But I’d certainly like to know.”

“Well, I’m into food history. I’ll look into it.”

It turns out that using cream of tartar in meringues is not only a fairly recent trend, but also likely of American origin. That being said, cream of tartar’s story truly begins, like all good stories, long ago and far away.

In which a Swedish chemist investigates 7,000-year-old wine residue

Cream of tartar, as previously mentioned, is purified wine residue–and the earliest known instance of said residue was found inside 7,000-year-old wine barrels in the Zagros Mountains of western Iran. This info comes from an excavation of “six vessels buried under the floor of a mud brick building of the Neolithic Hajji Firuz Tepe village.” (1) And it’s fairly guaranteed that the calcium tartrate inside the vessels–the unprocessed version of cream of tartar–came from grape juice, as, according to the excavation document, “there is no other common natural source.” (1)

Thusly it was found. But the life of calcium tartrate was fairly unremarkable until Charles William Scheele (also known as Carl Wilhelm Scheele) came along–the Swedish chemist credited with isolating cream of tartar in its current form. According to his biography, he isolated tartaric acid from cream of tartar and “ascertain[ed] many of its properties” in 1768. (2)

“Cream” is a little murkier. However, since it’s partially derived from Late Latin chrisma meaning “ointment,” and from the 1500s onward meant both “most excellent element or part” and “any part that separates from the rest and rises to the surface,” it’s a short leap from “purified form of tartar” to “cream of tartar.” (4)

So from barrels in Western Iran to chemistry labs in Stockholm, cream of tartar traveled. But at what point did people start baking with it?

In which cream of tartar is medicinal, probably

The 1886 American Encyclopedia of Practical Knowledge describes cream of tartar as “used extensively in medicine and in cookery,” and says that “its medicinal properties are numerous.” For example, it’s a cooling laxative, a diuretic, and used to help with skin diseases…mostly in farm animals, apparently, since the end of the paragraph gives the proper dosage for cattle (2 or 3 ounces), sheep (½ to 1 ounce), and dogs (5 to 20 grains). (5)

Around this same time, cream of tartar was listed in a London recipe for candied oranges, a semi-strange, let’s-just-throw-this-in-boiling-sugar use. (6) But far more commonly, cream of tartar was used in baking powder.

In which cream of tartar is used in baking powder

There are hundreds of examples of cream of tartar being used as a leavening agent for cakes, cookies, puddings, and just about any other place you would use baking powder today. For a while, cream-of-tartar-based baking powders were the only game in town, and women were making them at home by mixing together cream of tartar and baking soda. (7, 8)

Why did this work? Remember those vinegar-and-baking-soda volcano science projects from elementary school? When baking soda is combined with an acid, it produces carbon dioxide gas–and cream of tartar is 100% acid. In batters, the gas creates air bubbles that make the batter expand; the expansion gets set when the batter is exposed to heat. (9) (Sidenote: If you want a full scientific explanation of how cream of tartar affects food, this Slate article is fantastic.)

In the late 1800s, some baking powder companies started using alum powder as a cheaper substitute for cream of tartar; cream of tartar had to be imported from Europe as a wine byproduct, while alum powder could be made with inexpensive minerals in the US. (7) Faced with razor-thin margins, cream-of-tartar baking powder started losing market share in a major way. At the time, Americans were buying 120 million pounds of baking powder annually, but only 20 million of those were cream of tartar; the rest were alum. (7)

Linda Civitello’s book Baking Powder Wars goes into significantly more depth, exploring the tug-of-war between the three main cream-of-tartar-based baking powder companies as they fought for control of an ever-diminishing market share; Royal, Dr. Price, and Cleveland. An ad in an 1884 issue of Ballou’s Monthly Magazine shows off the infighting: (10)

“Facts are stubborn things. –Is there anything in any of the numerous advertisements of the Royal Baking Powder to show that the Royal does not use Ammonia and Tartaric Acid as cheap substitutes for Cream of Tartar?…

Ammonia and Tartaric Acid produce a cheap, leavening gas, which is not to be compared…with the more desirable Carbonic-Acid gas generated by the exclusive use of the expensive Cream of Tartar.

Use Cleveland’s Superior Baking Powder, and judge for yourself of its superiority.”

While Dr. Price and Cleveland ultimately lost to Royal, the American Baking Powder Association declared in 1904 that “the entire south was irrevocably lost to cream of tartar and gained by the alum interests.” (7)

Interestingly, it was right in this window–1893, to be precise–that the first mention of using cream of tartar as an egg white stabilizer, and not a baking powder, appeared.

A brief summary of meringues before 1893

The battle between the cream of tartar baking powder companies took place mostly between 1888 and 1899. And up until this point, meringues existed, but they were totally uninvolved with cream of tartar.

Meringues are hailed as French and/or Italian, and since the United States imported their cream of tartar ingredients from Europe, it seems like cream of tartar would have found its way into a French or Italian meringue before an American one.

But in French and Italian cookbooks from the same period and earlier, directions for meringues were either some version of “prenez six blancs d’oeufs; battez-les en neige” (12) or “sbattete 6 bianchi d’uovo entro un bacina distagnato con un mazzetto di fili di ferro…” (13); loosely translated, “Beat your egg whites with a whisk until they reach ‘firm snow.’” These recipes then directed the baker to add sugar, bake, and serve.

For decades, this was the way meringues were made, at least according to cookbooks. American cookbooks left cream of tartar out of their meringue recipes, too–as far as they were concerned, all meringues needed were a healthy dose of egg whites, sugar, occasional flavoring, and an oven at a fairly low temperature.

Then, one cookbook changed that.

In which a cookbook by an ostensibly fake person marries cream of tartar and meringues

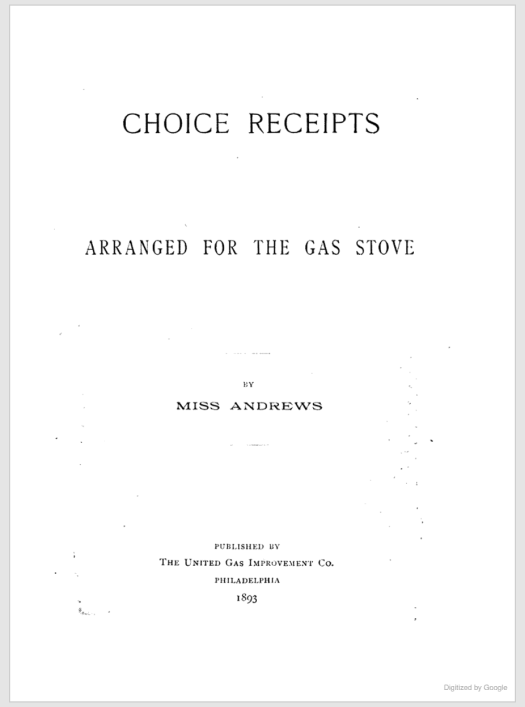

Which cookbook? Choice Receipts, Arranged For The Gas Stove. Written by an almost-certainly-nonexistent “Miss Andrews,” and published by the United Gas Improvement Co. (11)

Seems legit, no? The function of the cookbook was clearly to teach consumers how to use their brand-new gas stoves, given the explanatory first chapter that painstakingly describes the nuances of gas burners (i.e. Don’t light it until you need it!).

Fair enough. If you’re selling gas stoves, you want consumers to know how to use them. But the cookbook also bangs the “cream of tartar is a vital meringue ingredient” drum surprisingly hard. Miss Andrews’ definitive directions for meringues are as follows:

“…The eggs are beaten with cream of tartar (1-8 t. to each egg) until stiff and dry, and then flavored with XXXX sugar and a few drops of rose or almond; an excess of sugar in the egg reduces it to a liquid. 1-2 T. sugar to the white of 1 egg is a good proportion, and cream of tartar stiffens the whites…” (11)

This also extends to meringues used as pie or pudding toppings, as seen in the Apple Meringue Pudding:

“…Without drawing from the stove, cover with a meringue made from the whites of the eggs beaten with the cream of tartar and flavored with 2 T. pulverized sugar and the almond. Work quickly and brown lightly.” (11)

The inclusion of cream of tartar in this gas-stove propaganda lightly begs the question–were there any business ties between Royal Baking Powder and the United Gas Improvement Co.? The closest tie seems to be C.N. Hoagland, who was vice president of Royal (7) and on the board of directors of the Edison Electric Illuminating Company (14), which, oddly, seemed to be a competitor of the United Gas Improvement Co. (15).

Could the Hoaglands have cut a low-key advertising deal with the United Gas Improvement Co. to publicly diversify the uses of cream of tartar? In a market where cream-of-tartar-based baking powder was being quickly replaced, it’s not out of the question–but without further proof, it sounds a little too much like a cream of tartar conspiracy theory.

Regardless, Miss Andrews’ Choice Receipts seemed to be a one-off idea that didn’t hit the mainstream…at least until the 1960s.

When meringues finally start using cream of tartar on the reg

A 1961 New York Times article gives out “simple rules” for the “perfect meringue”–and included in these simple rules? Cream of tartar. (16) In 1969, an issue of the South African Sugar Journal printed a recipe for Apricot Meringue Surprises that included cream of tartar. (17)

But perhaps the most important meringue recipe of the time was Craig Claiborne’s “M-m-m-m–meringue” in the New York Times, which used–you guessed it–cream of tartar (18), and more importantly, was written by “The Man Who Changed The Way We Eat.” (19) Claiborne was a hugely influential food critic, and in 1979, Bon Appetit started printing recipes using cream of tartar as egg stabilizers; to make light-as-air cakes (20), praline chips (21), and, yes, meringues (22, 23).

Gourmet picked it up (24) and other magazines followed suit–and today, cream of tartar is de rigueur in meringue recipes in cookbooks, blog posts, and pastry schools.

Sources

- Essentials of Botanical Extraction: Principles and Applications

- The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions

- Etymology Online: Tartar

- Etymology Online: Cream

- The American Encyclopedia of Practical Knowledge

- The Book of Preserves

- Baking Powder Wars

- Miss Parloa’s Young Housekeeper

- What Is Baking Soda?

- Ballou’s Monthly Magazine

- Choice Receipts, Arranged For The Gas Stove

- La Bonne Cuisine Francaise: Tout Ce Qui A Rapport A La Table Manuel-Guide Pour La Ville Et La Campagne Plus De Deux Cents Dessins Speciaux. Emile Dumont. 1889.

- Trattato di Cucina, Pasticceria Moderna: Credenza E Relativa Confettureria di Vialardi Giovanni, Aiutante capo-cuoco e pasticciere. Delle LL. MM. Carlo Alberto di Gl. 1854.

- Electrical World

- Electricity: A Popular Electrical Journal

- New York Times, “Perfect Meringues Possible By Following Simple Rules.” Nov 29, 1961.

- The South African Sugar Journal, page 852. Nov 1969.

- New York Times, “M-m-m-m–meringue.” May 17, 1970.

- Washington Post, “The Man Who Changed The Way We Eat.” Jun 15, 2012.

- Bon Appetit, page 130. Dec 1979.

- Bon Appetit, page 56. Feb 1980.

- Bon Appetit, page 30. Apr 1980.

- Bon Appetit, page 50. May 1980.

- Gourmet, page 62. Apr 1982.

- The Chemical Essays of Charles William Scheele

Photo credit: Annie Spratt//Wikimedia Commons//Wikimedia Commons//Wikimedia Commons//

I always wondered about cream of tarter. Thanks for telling its story. Have to laugh at it gaining popularity in the 1960s…a time responsible for SO many food trends!

LikeLike